My Abba (grandad) was a poet. He loved literature, a sucker for words crafted beautifully in Urdu, Farsi, and Arabic. This was the only thing he could bring with him when he left Pakistan in 1962 for the prospect of a better future in Great Britain, and it ended up being the greatest thing he instilled in his children and grandchildren. His name was Nazir Ahmed Qureshi and was one of the many people from the South Asian subcontinent to migrate to Britain as part of a growing workforce.

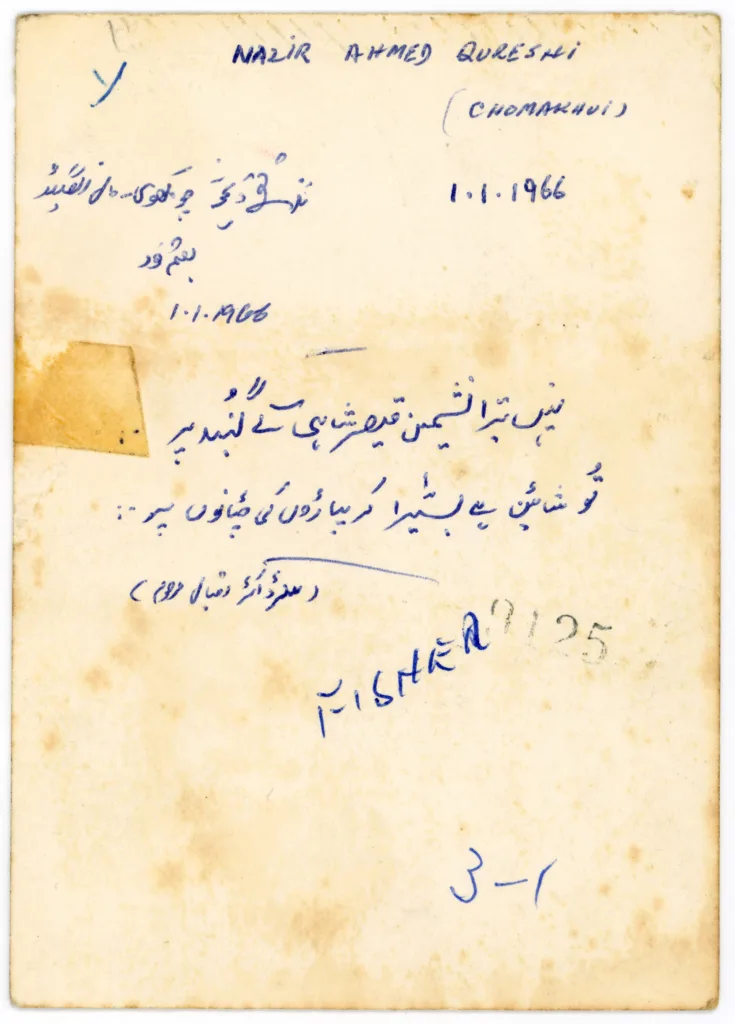

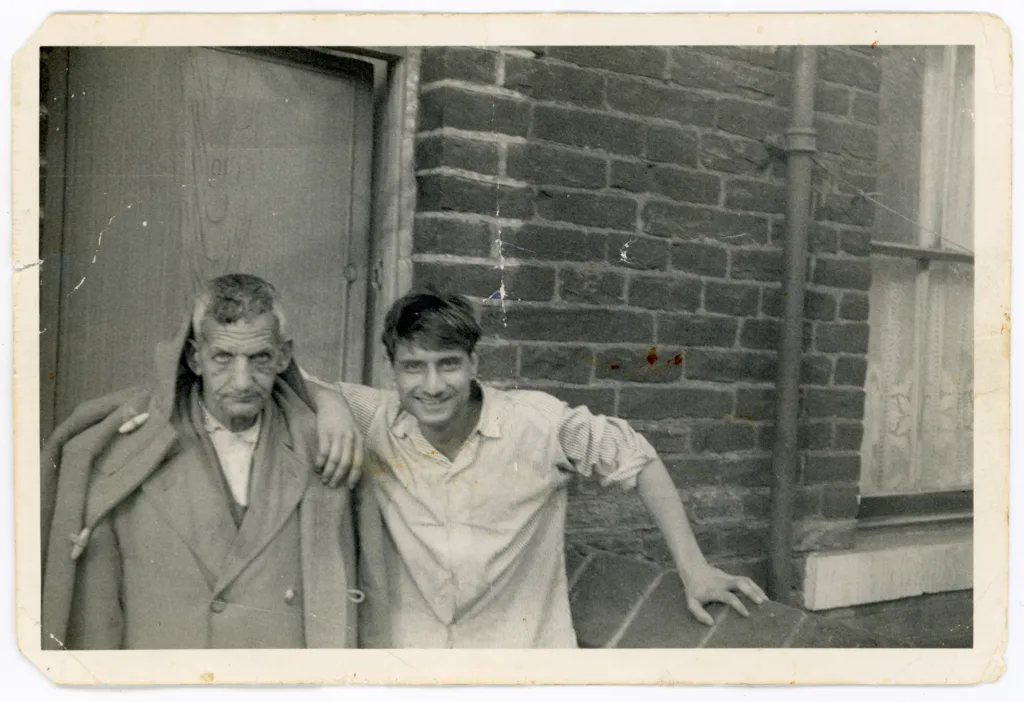

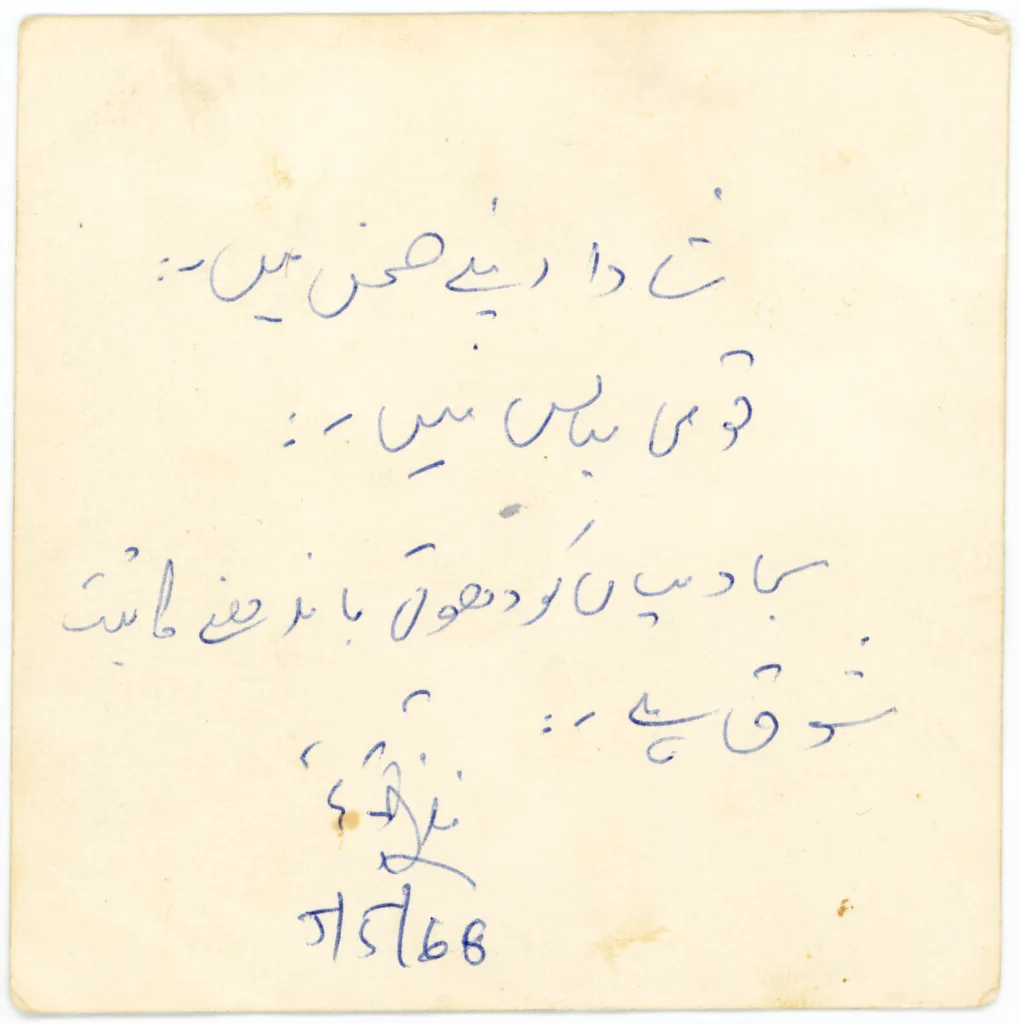

On the back of this early photograph, my grandfather jots down a couplet from the poet Allama Iqbal:

‘The abode is not on the dome of a royal palace; You are an eagle, and it should live on the rocks of mountains’.

This poem embodies the journey that my grandfather and others like him undertook; the desire for selfhood and freedom, and the courage to leave the comfort of culture and family for something new. It was not easy, but it was right. The journey of my Abba is a story of doing what was best for his family, but also cultural and spiritual integrity. Amid adapting to survive a new, and perhaps harsh climate, he held on tightly to his identity and faith.

This poem becomes symbolic of the purpose of my Abba’s migration and what he wanted for me and the rest of his grandchildren. He endured the mountains so that we could have the strength to fly even higher, without forgetting where we came from. This is his story.

In 1961, my grandfather was desperate to be amongst those leaving for work in Britain. The British Nationality Act 1948 gave commonwealth citizens the right to live and work in Britain. Post World War Two, there was a recruitment drive in South Asia for several key industries in Britain. My grandfather was one of those recruited to the textile industry in Bradford.

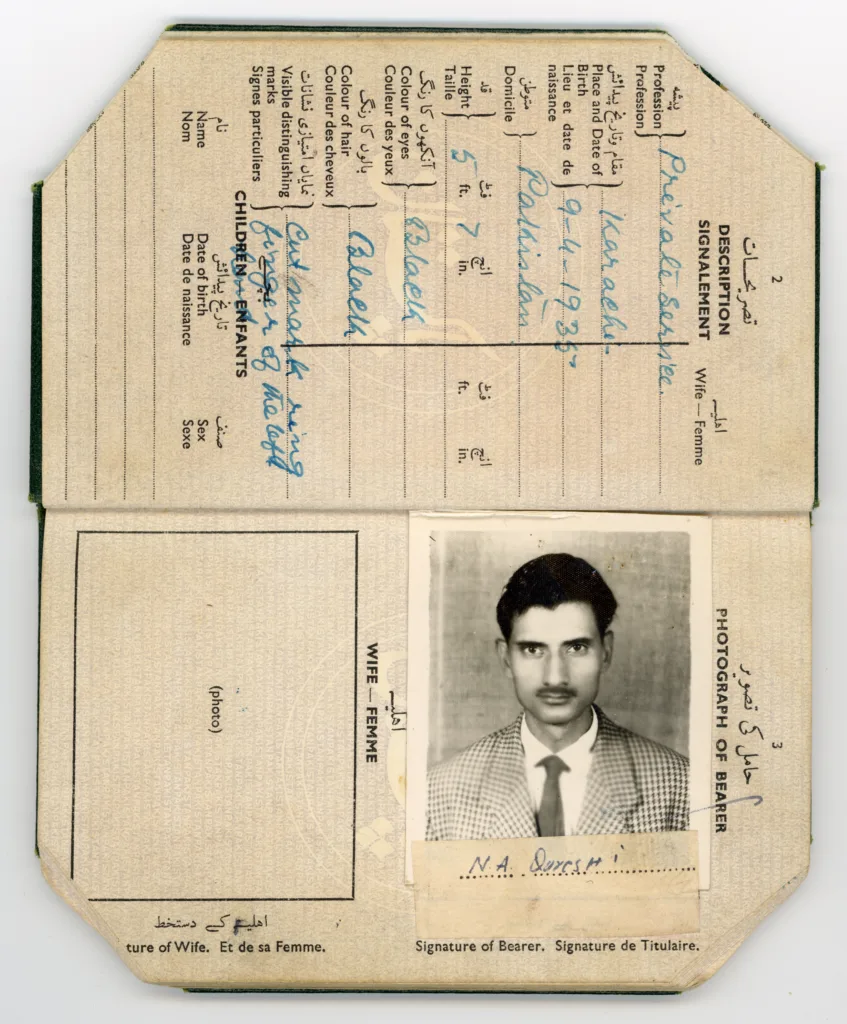

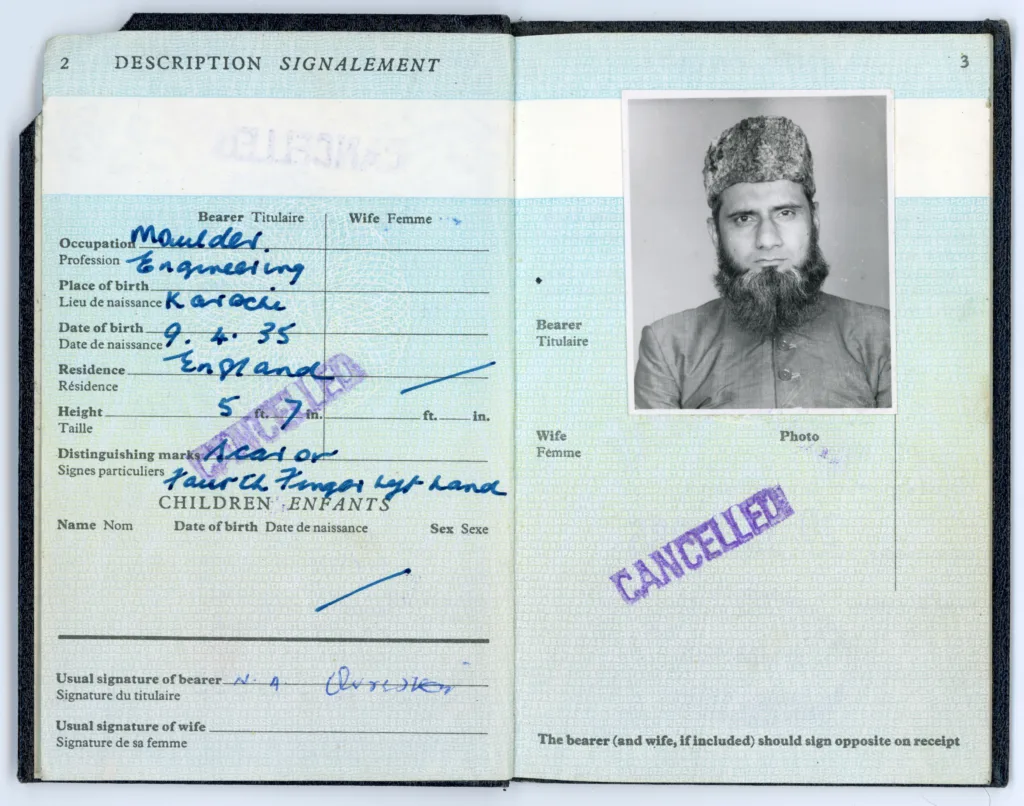

His father, however, was hesitant to allow him to go. He did not want all his sons to leave the land where they were born. His younger brother, affectionately known as Pa, and his elder brother, Jee, were both making their preparations to leave. My aunts tell me how Abba had wanderlust. He ran away to Karachi to have his passport made. My aunts laugh when they tell me that this is why my he looks so frail in his passport image, “He hadn’t been eating properly after that long journey!”. It was his wanderlust that kept his belly full. My grandfather managed to then convince his father to let him leave with his brothers, and in 1963 he left for Britain without knowing if he would ever return permanently.

My grandfather worked long hours in a factory in Bradford, alongside his younger brothers. Like many others, he adapted to a new environment, wearing smart suits and ties to fit in. In his passport photos, you see his change in appearance over the years, as his identity changed and developed. His change in dress, and the confidence to appear more visibly Muslim and Pakistani comes later in this story.

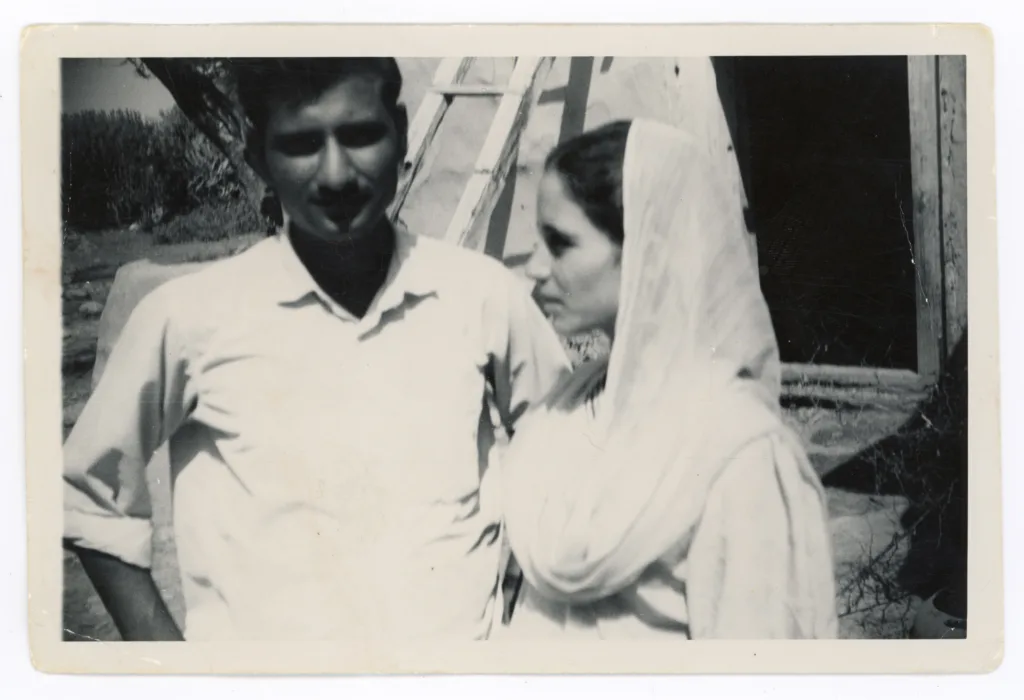

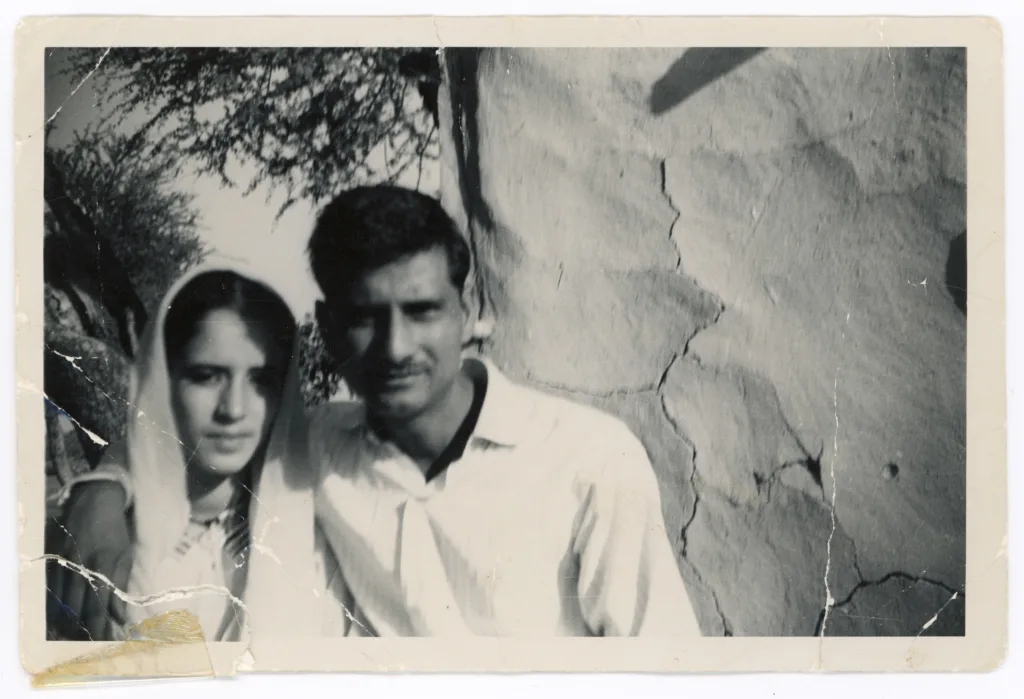

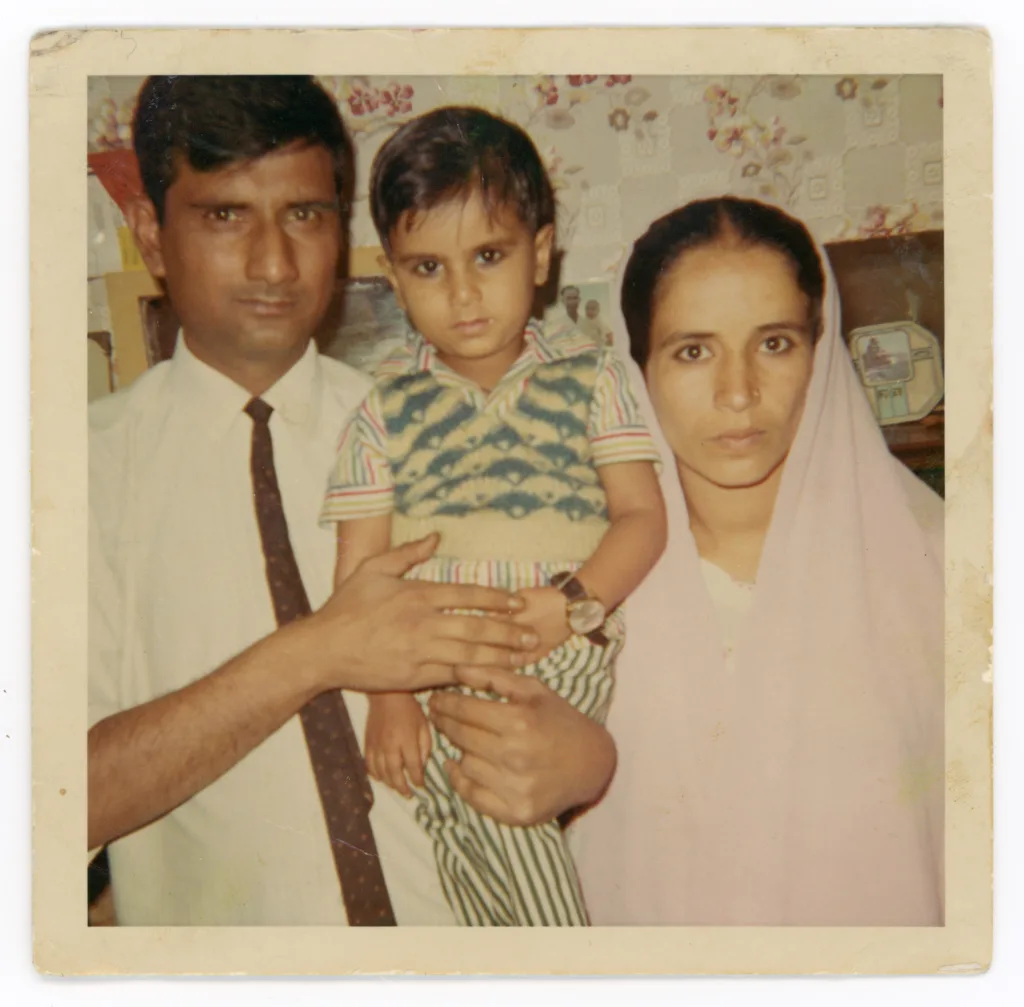

My Abba got married to my Amma, Najam-Un-Nisa, in one of the back-and-forth trips to Pakistan. Suddenly it was clear, the reason for the move and search for a better life.

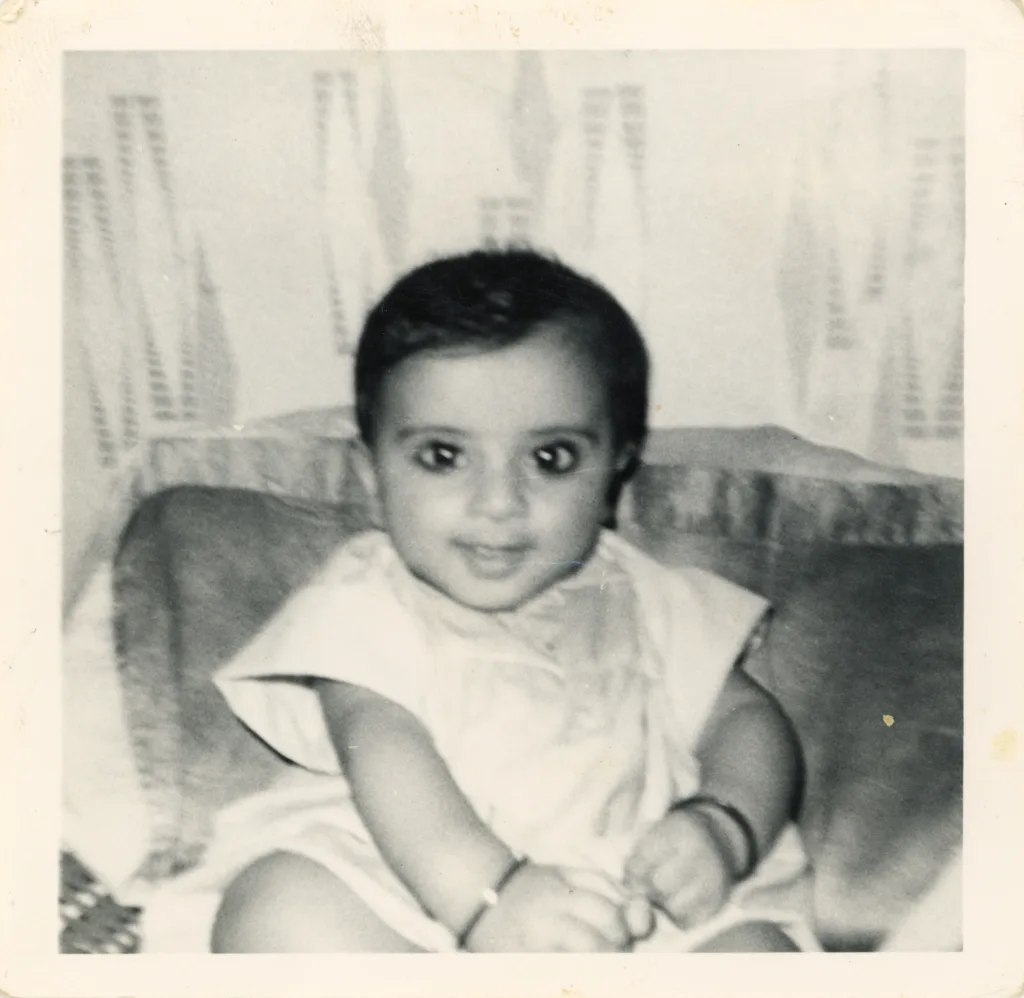

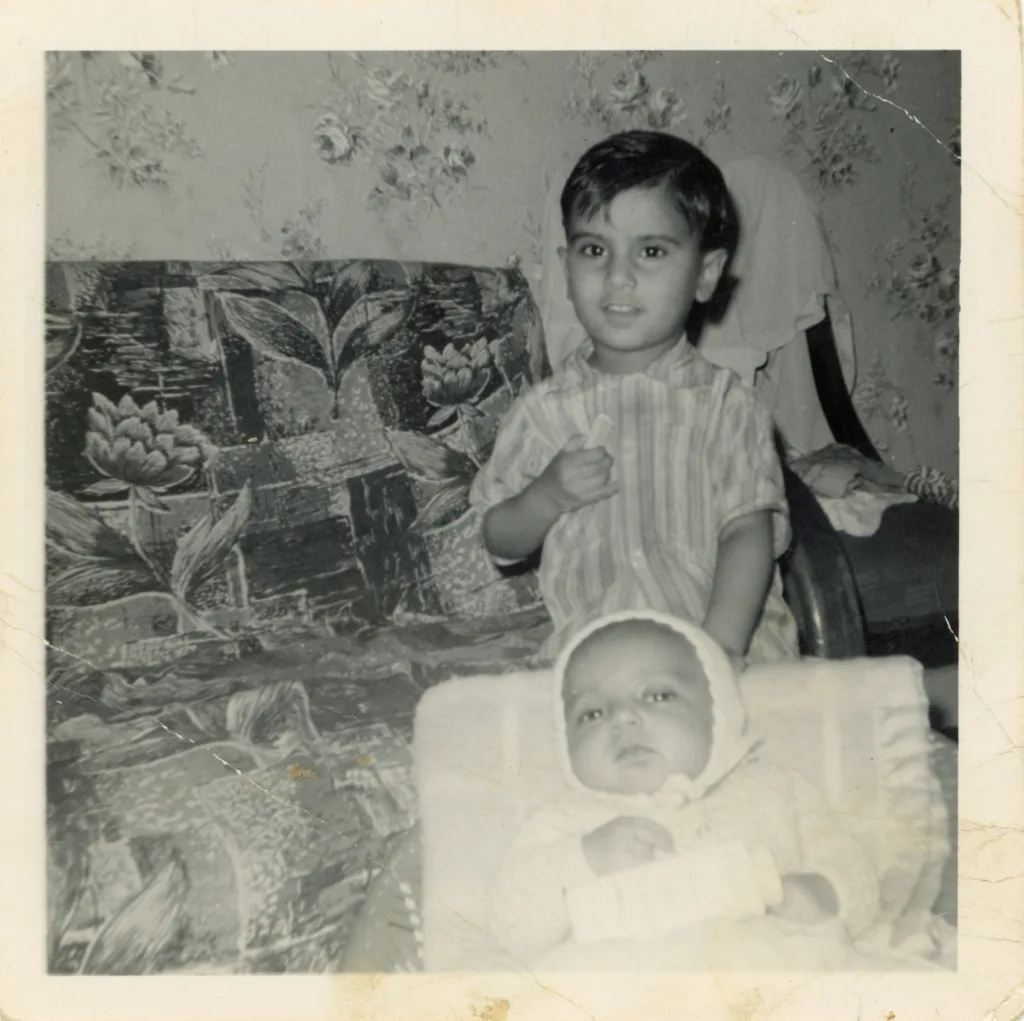

My Amma quickly became pregnant with my Taya (uncle) Sujad, who was born in 1965. My Abba found his purpose. He didn’t know it then, but he would become the head of a large family of 6 children, with lots of grandchildren at his feet, who he would sneak sweets to. My Amma joined Abba in Bradford in 1966 with small Sujad in tow.

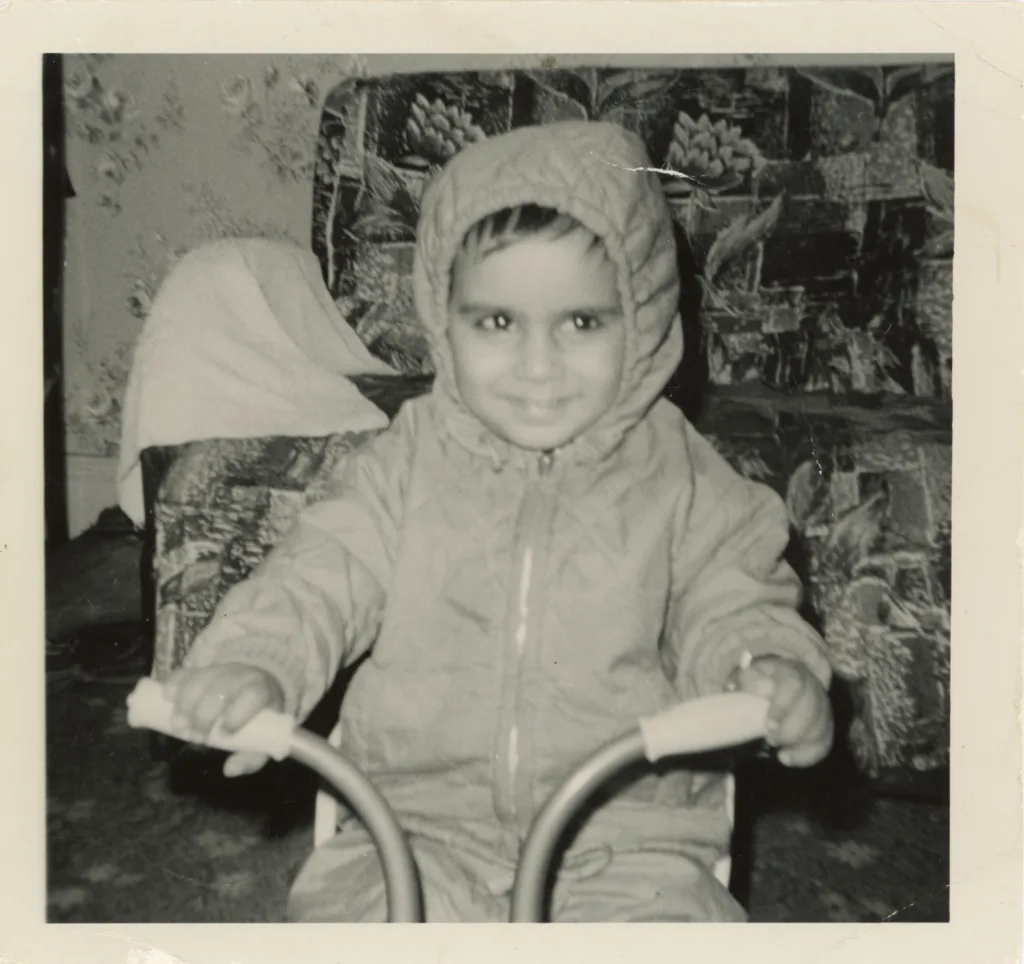

Abba would affectionately write small notes on the back of the family photographs, explaining who, and what they were doing and dated them. (I might have gotten my historian in me from him, thanks Abba!) This photo says, ‘Mr Sujad is fond of wearing traditional clothing’.

After moving to Britain, Abba and my beautiful grandmother settled with Sujad, their first child. My Taya (eldest uncle) Fiaz was born, and then my dad, Ayaz was born in 1969. My grandmother took on the role of looking after the household raising three boys and took care of finances. My phupo (aunty) Shamsa followed, and then my uncle Ajaz. My Phupo Fozia was the last of the troop, and arguably my grandad’s favourite, born in January 1985.

The wanderlust in Abba’s soul never waned, it deepened alongside his growing spirituality. As a devoted member of the Tabligh-Jamaat, a Muslim group that encouraged connection to faith, he travelled widely, serving as an Imam in mosques around the world in the company of fellow Muslims. In Bradford and across the district, he became a foundational figure of the local Muslim community. Not only did he welcome new arrivals to Britain but created a sense of belonging built on his understanding of what it felt like arriving in an unfamiliar place.

With his elegant Urdu and Arabic calligraphy, he created signs for mosques and gatherings. A skill so exceptional, it earned him a position teaching Urdu and calligraphy to teenage boys. His legacy became firmly rooted in the community he helped shape. Many of his former students went on to establish their own mosques, often recalling him as a mentor and an enduring inspiration.

My grandfather’s life was a testament to resilience, strength and unwavering faith. He held a deep conviction that the women in his family should be educated, a goal he carried with quiet, yet resolute determination. One of the last things he said to me before he passed away was ‘Ramlah beti, read, read, read, until you can no longer bare it.’ I believe he, and my Amma would be proud to know that their daughters and granddaughters have become the most educated women in our family’s history. He was a poet, and now his granddaughter carries forward his voice, telling his story.